Citibank: Why one of the world's largest and most iconic banks is wrapping up its retail business in India

While the bank's exit from its consumer banking business in the country is part of the group's plan to utilise capital resources better, it is also reflective of the intense competition foreign banks face in India while taking on domestic heavyweights

Pedestrians walk by a Citigroup Inc. bank branch in Mumbai, India. Image: Kuni Takahashi/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Pedestrians walk by a Citigroup Inc. bank branch in Mumbai, India. Image: Kuni Takahashi/Bloomberg via Getty Images

It is a partial goodbye for one of India’s oldest foreign banks.

On April 15, Citigroup, the New York-headquartered $151 billion financial services company announced its plan to exit the lucrative retail banking business in India as part of an ongoing strategic review of its business. Citibank had set foot in India some 119 years ago when it started operations in then Calcutta, part of British India.

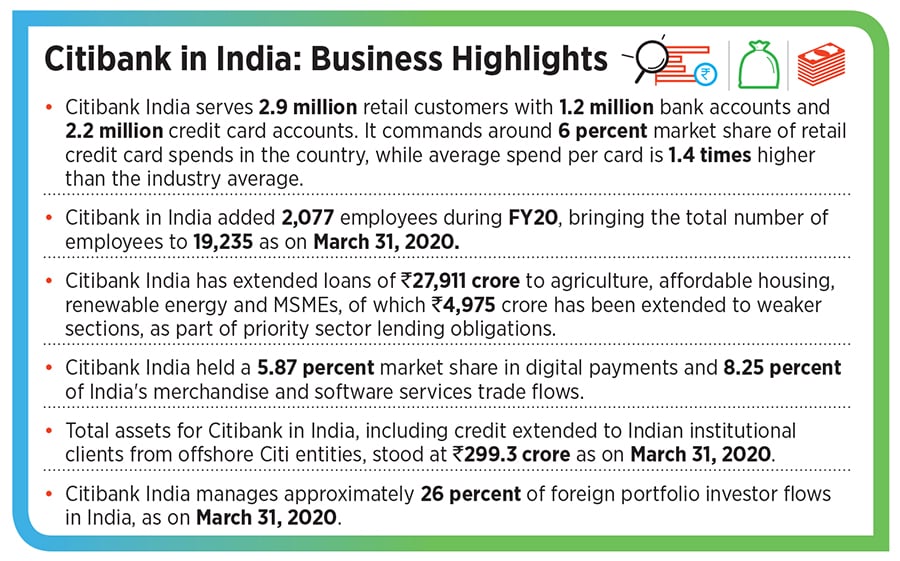

A century later, the company had built up a business covering some 2.9 million retail customers, 1.2 million bank accounts and 2.2 million credit card account holders. It has over 35 branches in the country, and employs nearly 20,000 people across divisions including credit cards, retail banking, home loans and wealth management in one of the world’s fastest growing economies.

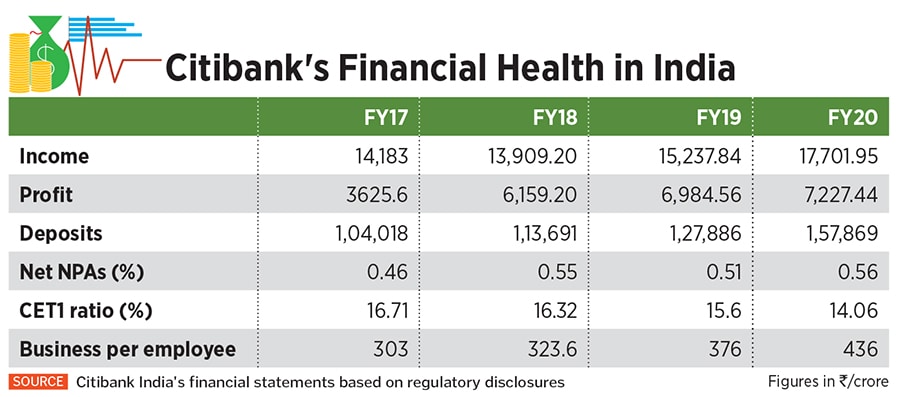

Over the years, the company had also built up a stellar reputation for pioneering India’s credit card movement, when in the late 1980s and 1990s, the company was among the first to offer the Indian consumer a slice of the plastic money revolution. That was soon followed by mortgage and personal loan offerings. Today, the company’s total assets, including credit extended to Indian institutional clients from offshore Citi entities, stand at Rs 299,250 crore as on March 31, 2020, while it has a deposit base of about Rs 1.57 lakh crore.

The company’s exit from India is part of the group’s plan under a new CEO to direct investments and resources to businesses in four key locations where it foresees huge scale and growth potential. That includes Singapore, Hong Kong, the UAE and London, and as a result it will exit its consumer banking business in 13 markets including Australia, Bahrain, China, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Poland, Russia, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam.